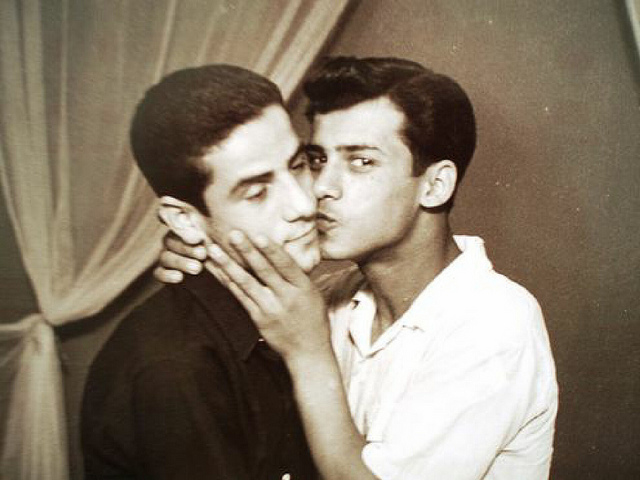

Men embracing and kissing. Robert Gant, ca 1887-1889

My dear, I don’t care what they do, so long as they don’t do it in the street and frighten the horses

(Mrs Patrick Campbell, c1910)

When it comes to romance and erotica, in my opinion there is enough trouble, enough heartache in the world without adding the tragedy of homophobia. I don’t enjoy erotic stories where people agonise for half a book, are frightened of or confronted by their sexuality because they can’t accept themselves, or homophobic characters make their lives hell. I like sex to be fun, romance to be nice, and neither to be guilt-ridden. So I don’t write gay angst or gay hate.

But I am often astonished by people’s general understanding of queer* behaviour in a historical context. I hear statements such as “people were too frightened to be open”, and “but it was illegal”. It seems to me people think queer people in history lived in hiding and every one of them suffered, denied, or hated their nature. And that homophobia was somehow worse than it is today.

Not so. For every person who suffered life-long self-loathing of their queerness, there were plenty who got over it or never suffered it at all. And haters will always be haters. I think this false belief is driven in part by the sexual regression that reached its crescendo in the 1950s. Homonegativity was its tragic outcome, which resonates even today, making us think life had always been that way.

Even today, many queer people were discreet, when the person has a social position or a job that could be at risk by being out. If you don’t want to attract homophobia in countries where being queer is not a crime, you keep it private. In countries where it is still illegal to be gay, even more discretion is usually practised. The past was not much different. Historically speaking, if they played the game, society largely left queer people alone.

Sure, there were times when it was dangerous to openly engage in homosexual activity, but this is not true for most of human history. History is not made up of homogeneous thought, there was not one outlook for the thousands of years humans have been around, even within one culture. Just as fashions come and go, morals change and attitudes cycle; yesterday’s heresy becomes today’s belief becomes tomorrow’s out-dated thinking.

In general, it is no safer to be queer now than it was during most of the last two thousand years of under the yoke of Christianity. There were periods of time when homosexual behaviour was as open and accepted as it is today. Just as there were periods when, just like in some countries today, queer people were persecuted, shamed, and murdered for the crime of being different.

Fanny and Stella (Frederick Park and Ernest Boulton) in 1868. The trans women were prosecuted in 1870 for “conspiring to incite others to commit unnatural offences” but acquitted after a doctor could not prove they had had anal sex with each other.

Homosexuality in history

Historically, sodomy was illegal in many cultures, and often punishable by death. Even in ancient Greece and Rome, where homosexuality was a prominent part of the culture, there were laws prohibiting sodomy. The historical definition of sodomy in post-Roman Europe included MM and FF sex, bestiality, male rape, oral sex, and child abuse. In fact, anything that was not a man vaginally penetrating a woman.

Across Europe from the time of the late Roman Empire, laws were enacted declaring some or all homosexual acts to be illegal, and ascribing various legal punishments from fines to public execution. And yet, actual organised systematic persecutions of people engaging in homosexual acts are few and far between.

That is not to say there was not persecution of individuals, but the extent of it is misrepresented, shamefully in some cases by historians. Yes, sodomy was illegal and sometimes people were brought to court for it, but so were having a different religion, adultery, sex before marriage, birth control, having a child while unmarried, and witchcraft, just to name a few things not illegal today (although still illegal in some countries, as is homosexuality). Some of these things were also punishable by death. People still did them all, sometimes quite openly.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, sodomy prosecutions were rare and often tacked onto a raft of other crimes the individual was being prosecuted for. Convictions were even rarer. “Molly houses”, brothels for gay men, were well known and rarely raided. Presumably law enforcement did not want to accidentally arrest politicians or other influential men.

Various naval forces are particularly rich with source material about sexual activity between men. In possibly the first glimmer of a DADT policy, some courts martial boards, regardless if the verdict was guilty or not guilty, expressed their displeasure that the activity was even brought to their attention!

.jpg)

WWII sailor boyfriends photographed for the Kinsey Institute at a time when it was illegal to be gay, and grounds for a dishonourable discharge. The NSFW version of this picture can be seen here

When studying the evidence, it becomes clear consensual homosexual activity was ignored or tolerated far more often than it was persecuted and condemned. The move to decriminalise homosexual behaviour began literally hundreds of years ago. In some countries, it was decriminalised, in others, the death penalty was removed (in the UK, the death penalty was not imposed after 1836, and was removed in 1861). It was not unknown for men of means in same sex relationships to move abroad so they could live more openly.

Fun fact: Decriminalisation of homosexuality in the 18th/19th centuries

1791 France—and who wouldn’t want to live there with one’s true love!

1811 The Dutch Republic and the Dutch East Indies

1830 Brazil

1852 Portugal (recriminalized 1886)

1858 The Ottoman Empire and Timor-Leste

1865 San Marino

1871 Guatemala and Mexico

1886 Argentina

Blackmail, the big danger

The biggest danger for most men was the threat of blackmail, but that could occur whether you had committed “unnatural acts” or not. Blackmail rings extorted money from victims with the threat of court action, and naturally had a plethora of false witnesses to the supposed crime. There are plenty of cases where blackmailers were prosecuted and executed for their crime of robbery, and whether their victims were literal bystanders or men cruising beats is not entirely clear. Men in a stable relationship, that is not cruising or going to molly houses, were unlikely to be targeted by casual blackmail.

Men could, however, be blackmailed by a former lover although the lover would have to incriminate himself as well. Often the worst that would happen with this kind of blackmail was loss of your job and reputation, not jail or execution.

It was even recognised in the nineteenth century that existing laws were making blackmail easy, and was a strong argument for repealing them. This kind of blackmail went on until the repeal of homosexuality laws, but certainly did not stop men from having relationships or casual sex. We know from letters, photographs, and other sources that men continued to engage in loving and/or sexual relationships with each other.

Laws will never stop love or lust!

Two men embracing. Probably photographed by Robert Gant between 1887 and 1889

Gay identity

Sexual orientation as an identity is a relatively new phenomenon which started to emerge in the late nineteenth century. In the past, you identified and were identified as a man or a woman. Angst over identity did not really exist, because there was no queer identity!**

Historical authors who portray it are putting a modern sensibility into a historical context because we can identify with it, not because it’s accurate. Read some contemporary literature with homoerotic themes—Melville’s Moby Dick, Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, Tennyson’s In Memoriam, Taylor’s Joseph and His Friend: A Story of Pennsylvania. The relationships may be coded, but they are accepted (and justified by contemporary critics). The characters (and the authors themselves) are sometimes troubled by their preference, but there is no agonising over the true self.

Recent history

When was all homosexual activity decriminalised where you grew up? You might be surprised to find out.

Where I grew up, homosexuality was illegal until 1990. Throughout the 1980s the police could and did actively persecute gay men for their private activities. That is, being gay in their own homes – yes, police actually raiding their homes and arresting them for what they were doing inside. In the 1980s.

And yet, according to my sources, the pre-HIV era in my hometown was a total gay shagfest. There were beats everywhere, men lived together openly, there were gay bars—one recently celebrated its 30th birthday (for those of you who are non-mathy, it opened in 1985, when the police were in full swing, so to speak). They just didn’t walk down the street holding hands, kiss in public, or any of the things straight couples could do (many still don’t).

Ask any gay man who lived as a gay man in the fifties, sixties and seventies. Unless you come from one of the countries listed above, homosexuality was probably illegal where you grew up back then. He’ll tell you he wasn’t necessarily open or overt, but he didn’t spend his life hiding in fear of being stoned to death either.

In conclusion

Until the latter part of the twentieth century, homosexuality was illegal in the US, the UK, and most former Empire nations. Although it was rare, you were in danger of being prosecuted. You could also lose your job, you could be blackmailed, your family could reject you, you could be bullied or beaten, you could be murdered by homophobes who then got away with it because you brought it on yourself. None of the examples in these links are pre this millenium.

People today use the illegality of same-sex activity as evidence that in the past, homosexual men lived furtive lives full of fear and self-loathing. This is simply not true. While anti-sodomy laws were being passed by the church and state across Europe, monks and bishops were writing love letters to each other, kings and nobles were openly living with their lovers, married men were carrying on same sex affairs and visiting male prostitutes. From Roman times, there has been a rich gay subculture in Europe, brought to the Americas. Occasionally queer people were harassed, but mostly they were left alone.

*This rant does not include lesbian activity—in many places were homosexual activity was illegal, lesbianism was neither acknowledged nor illegal. It was therefore by default legal.

**This does not include transgender/intersex people who would have had trouble identifying in a binary male/female world. As I don’t tell their stories, I have never researched the issue.